| |

|

The Wednesday Night Drawing at the Palace Theatre

By Karl Taylor

The date is July 5, 1950. The time is 9:27 PM. The place is the Palace Theatre in Elmwood, Illinois, a small country town, west of Peoria, filled with retired farmers and factory workers.

The first picture show began at 7 PM, and the second will commence shortly when the drawing is over. Arwin Archibald, a part-time employee in the projection booth, is rewinding the film: a newsreel, a cartoon, and the main feature, a mystery movie. The scratchy newsreel is about increased tensions along the 38th parallel in Korea and the cartoon features Road Runner, the strange looking chicken that races cars and motorcycles down dusty roads. James Cagney, the little man with the big part, stars in the feature, his latest gangster movie, “Public Enemy.”

As the stage lights come on, 20 or 30 kids, from 6 to 16, crowd along the waist-high edge of the stage, as Eddie Hahn, the proprietor, pushes a homemade drum made of chicken wire to the center of the stage. He gives the drum a spin, and then another, as the cards with names, addresses, and telephone numbers tumble, end over end. Almost immediately the children raise their arms high and begin chanting in unison: “Eddie, Eddie, Eddie, Eddie.”

Eddie looks down the row of children, mostly young boys in crew cuts, and points his skinny index finger at Jack Jordan, who jumps up on the stage, facing the audience. Momentarily he is blinded by the stage lights, but he tries to find a friendly face in the audience,

|

maybe Dick Whitney or Tom Jones. At Eddie’s command, Jack reaches into the drum, drawing out a ticket for a $25 prize to anyone present. Without a winner, the prize increases $25 for the following week. For his work, Jack earns 25 cents, enough to buy a ticket to the next movie, a box of popcorn, and one cent to spare for a piece of candy or bubble gum at the Fair Store, the five-and-dime less than two blocks away.

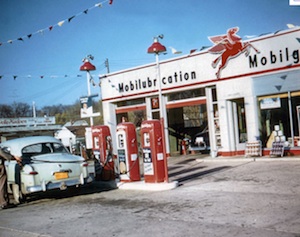

In 1950, the Palace Theatre is one of the busiest places in town. Located at the corner of West Main and South Lilac, the Palace is situated across the street from Cisel’s Mobil Station with the flying red-winged horse, Howard’s Standard Oil Station with the white and red crowns, and the Neptune Fire Department. The latter is a two-story red brick structure built in the later half of 19th century, housing two fire trucks on the first floor and city council chambers and rehearsal space for the Elmwood Municipal Band on the second floor.

The Palace attracts customers from surrounding areas: some travel by gravel road from Williamsfield (population 600), by black top from Brimfield (900), and still others by “hard road” from Yates City (600). On Friday and Saturday, customers come to see the Lone Ranger with a black mask and white hat and his famous sidekick, Tonto; Gene Autry and his pal, Smiley Burnette; or Roy Rogers and his palomino horse, Trigger. On Sunday, Monday or Tuesday, people like the Websters from Laura or the Whittakers

from Princeville are eager to see Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers dance lightly across the stage or to fantasize about Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. And on Wednesday and Thursday nights, adults and some kids (they should be home studying or in bed) are attracted to the mystery and, of course, to the drawing. |

Movies, in the 1950s, are intended to be enjoyed for the moment and forgotten, not analyzed and psychoanalyzed. Life is simple; movies reflect that simplicity.

No matter what evening they choose, buying a ticket and refreshments follows the same sequence: the customers open the colored doors (sometimes lavender, other times pink) with the heavy chrome handle and stand in single file by a poster advertising a “Coming Attraction.” Sometimes Gregory Peck, sometimes John Wayne. They edge closer to the ticket booth where Vivian Hahn, Eddie’s white-haired wife, or Vera or Ernestine Bateman, her blue-haired friends, sell tickets – 14 cents for children or 44 cents for adults. Vivian is a short, very enthusiastic woman who talks to customers no matter how busy, no matter how long the line. Vivian says more in one day than her husband says in a month. He’s quiet.

Two steps away from the ticket booth is the popcorn stand, the kind with the round popper hanging from the top, requiring the operator to dump the hot popcorn into the bottom of the stand. Carefully the operator – generally a high school boy – scoops the delicious yellow-colored corn into a rectangular box, right and white, with lids on each end. Hot, buttery (who ever heard of cholesterol), the corn is worth $5 a box, but it sells for a dime.

With refreshments in hand, the customer’s next choice is deciding where to sit – on the main floor or in the balcony. Generally adults – both singles, young couples --and kids up to the age of 13 or 14 – sit on the main floor. The balcony is unofficially reserved for teenagers. |

When young men or women enter high school, they are qualified to sit in the balcony, where they enjoy a bit of privacy from their parents and young siblings. Groups of girls, usually giggling, sit on the left side; groups of teenage boys, usually watching the giggling girls or teasing them, sit in the middle of the balcony; and to the right are the teenage couples, going “steady,” who sit prim and proper in their seats, until the house lights go down. Quickly, the young men put their arms around their girls who cuddle in their arms. There is some kissing and a lot of “necking,” but serious policing is un- necessary. Nevertheless, the tall slender proprietor walks slowly down each aisle, pausing now and then, his flashlight pointed to the floor, making sure that chatter is kept to a minimum, that young lovers behave appropriately.

With the drawing completed, the theatre begins emptying. The teenagers come bounding down from the balcony, sometimes colliding with parents and younger children leaving the main floor. Experienced customers exit through a side door. Outside the gas stations are dark, but the street lights provide plenty of illumination for the moviegoers to find their way home or to their cars.

They feel safe and secure because Arno “Slim” Dauma, the tall, skinny 70-year-old Elmwood policeman and former blacksmith, has parked his squad car across the street in Howard’s Standard Station. He keeps an eye on things. At least six feet tall and weighing less than 165 pounds, Slim looks like Barney Fife, the sidekick on the popular Andy Griffith Show on TV. Slim wears a dark blue “bus driver” hat, matching shirt buttoned clear to the top, dark blue pants, and black belt with holster, pistol, and night stick.

He leans back against his black Ford squad car, pulls out his package of Red Man, and stuffs tobacco under his lip. No doubt about it. He looks threatening, but he isn’t. |

He’s as gentle as a lamb. A part of his job is to direct traffic, both people and cars, when the movie is over.

As the doors of the Palace Theatre swing open, the bigger kids come out first, followed by the little ones and later the adults. The moviegoers spread in all directions, some walking to Central Park or Luthy’s Bowling Alley and others heading to their homes on Magnolia, Elm, and Walnut Streets. No matter what direction or destination they choose, in the dark or under the street lights, everyone is safe. Locked doors are unnecessary. Chaperones are superfluous. Slim is there.

Sixty years later, Elmwood still exists; movies are still shown at the Palace Theatre. But the people, who made the theatre live, are all gone – Arwin Archibald, the projectionist; the Batemans who sold tickets, and Eddie and Vivian, the proprietors. Slim, too, is no longer there.

One thing has not changed: the Palace Theatre is still a vital part of a small country town in Illinois. end

Karl Taylor was born, raised, and educated in Elmwood, Illinois. After graduating from Knox College and the University of Illinois, he taught English at Illinois Central College and worked as an administrator at Bradley University in Peoria. Karl’s father and mother operated The Penny Super Market in Elmwood for over 30 years and were good friends of Ed and Vivian Hahn as well as many of the other people mentioned in this memoir. |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

| 24th Infantry Division troops of Task Force Smith at Taejon railroad station on July 2, 1950. Photo: U.S. Army. Source: D.M. Giangreco, War in Korea: 1950-1953 (Presidio Press). |

- - |

| Gene Autry -- The Singing Cowboy -- Smiley Burnette |

|

| Butter made with Palm or Coconut Oil base |

|

| Photo on Sunday after Tornado looks good from this angle |

|

| Gary Cooper High Noon |

|

|

|

| Pegasus the famous Mobil Symbol |

|

| 1949 Ford Four Door |

|

| A real man's chew |

|

| I have oftened described Elmwood as a real Mayberry, young people don't know what I mean. |

|

|

|